Theatre

Weaving Stories of Strength, and Soul

In Pakistan’s evolving art landscape, few names resonate as deeply as Kulsoom Aftab, a director, dramaturge, poet, actor, and mentor whose artistry transcends boundaries. From her acclaimed Urdu translation of Stanislavsky’s “An Actor Prepares” to her unforgettable performances in Shakespeare’s ‘Antony and Cleopatra’, Kulsoom has carved a space where intellect and emotion coexist powerfully.

Q: You’ve worn many creative hats — director, actor, writer and dramatist. How do you switch between these roles, and which one feels most like home to you?

I don’t really switch at all. Most of the time I find myself doing everything, whether it’s my own projects or my production house’s work. For years, if I was acting in something, I’d also be asked to check the dialogues or handle production details. Only in the last couple of years have I had the luxury of just showing up as an actor, performing, and then going home.

But in theatre, I’m still my own ticket-seller, producer, director, and actor. Especially because I mostly do original plays or dramatic remakes which require that level of involvement. And honestly, theatre feels most like home to me. Whether I’m directing, acting, doing dramaturgy, or even just managing a festival, being in that space always feels right.

Q: Your Urdu translation of Stanislavsky’s ‘An Actor Prepares’ is a huge milestone. What inspired you to take on such classic and intense work?

Shararat! That’s really how it began. I had been teaching theory at NAPA for almost a decade, but I wanted to learn acting formally. When I went to Dr. Enver Sajjad and asked him what to study, he simply told me: “Don’t read. Just act.” But I insisted on reading theory first. He reluctantly handed me ‘An Actor Prepares’.

When I read it, I was shocked that such a foundational book on acting had never been translated into Urdu. It’s the first book that actually turned acting into an academic subject. I pushed Dr. Enver Sajjad to translate it, but he declined due to health reasons. Eventually, with support from our dean, Rahat Kazmi, I took it on. Dr. Enver translated half before his health declined, and I carried it forward. What started as mischief turned into a mission and eventually a co-translation.

Q: Why Stanislavsky, specifically?

Because it’s the source. Every major theorist after him stands on the shoulders of ‘An Actor Prepares’. Without it, acting education is incomplete. In Pakistan, we had institutions of performing arts but no Urdu translation of this fundamental text and that made me angry. It’s not just a manual, it’s an invitation to discover your own method. That openness is what drew me to it, and I do hope to translate the rest of the trilogy one day.

Q: You’re a strong voice for female empowerment and meaningful content. How do you see the industry evolving in that space?

I’m cautious when we say “evolving.” Women are mostly carving their own space rather than being given it. Institutions rarely make conscious efforts to place women in positions of creative or administrative authority. Yes, women are often welcomed in supportive roles, the ones that carry pressure but don’t demand credit.

Personally, I stopped trying to be responsible for every woman. I decided the one woman I must always answer to is myself. By doing that I found myself connecting with other women, telling them: ‘This was your right, you could have asked for it.’ My work has been grassroots, starting from my own institution, and slowly spreading outward.

Q: As a woman in the arts, what challenges have shaped your journey the most?

The biggest challenge was invisibility. I would sit in rooms full of men and hear, ‘We don’t have any writers.’ And I was right there. That hurt deeply, I cried at home sometimes but it never broke me. Somehow, life always gave me a chance to be seen again.

I tell young women this: don’t abandon your identity at the first sign of hardship. Many women do. They think it’s easier to hide who they are, but that phase as difficult as it feels is just one part of the journey. If you hold on, there’s always another step waiting that can change everything.

Q: Your documentary ‘Our Jacob’ won hearts. What was the most powerful moment for you during its making?

The irony is, I wasn’t supposed to write it at all! The concept was by Naseem Himoz, but when he fell sick close to the deadline, I had to step in. I wrote the first draft in a single night, then refined it later.

What struck me most was the people of Jacobabad speaking about John Jacob a British officer who gave the city its name. They spoke of him as a healer, almost a saint. To this day, people visit his grave, believing threads tied there can cure back pain. It was fascinating to see how a colonial administrator became a figure of local spiritual reverence, and how deeply people protected his legacy. That was the emotional core of the documentary.

Q: How do you balance your work between stage performances like ‘Antony and Cleopatra’ and more intimate mediums like documentaries or poetry?

I don’t balance at all. Poetry comes when it wants to; you can’t summon it. Acting on the other hand, is deeply intimate and consuming. Honestly, no artist can work by ‘balancing.’ We work like mad people sixteen hours a day. When the pandemic forced me to pause in 2020, it was my first real break in ten years. There’s no balance because creating requires both survival and luxury. You must earn to live, but also create the illusion of having time, space, and beauty to write. It’s constant juggling.

Q: Your last play at NAPA, ‘The River’s Daughter’, was a powerful production. How was it received?

The response was overwhelming. At a time when theatre audiences in Karachi were shrinking, this play managed to pull people back in. And that success wasn’t just mine it was collective. Seniors, mid-career artists, students—everyone at NAPA contributed.

What made it special was that it was an original play, and unfortunately, there’s a bias against original writing in theatre. Even respected teachers and colleagues often avoided it. ‘The River’s Daughter’ broke that pattern. It had a powerful script, a versatile cast including Aamina Ilyas’s debut and Sheema Kirmani, and a troupe of folk musicians who brought raw authenticity. For me, that was the highlight, making folk singers feel at home in a theatre space, and making the production truthful in a Stanislavskian sense.

Q: You work closely with aspiring artists as a coach and student counselor. What advice do you find yourself repeating often?

The first thing I tell them is to read and not just books, but themselves. Self-reflection is the starting point of any artistic journey. Second, I remind them to take their work seriously. Not every moment is for laughter; discipline matters.

Third, silence—our art is built on silence. A performance can cost crores in lights, makeup, and production, but if one actor needs focus and another distracts them, it destroys the worship of the craft. Whether in theatre or on screen, silence is sacred. Many young students struggle with this, but it’s crucial. Fourth, I stress originality. Don’t copy. Your original idea will always carry more power than any adaptation.

Q: You have also started your own private academy. Please tell us about it.

Yes, it’s called Theakada (Theatre K Academy of Dramatic Arts Karachi), launched earlier this year. I had already founded Theatre K Productions back in 2012, but Theakada is my second more ambitious venture, a creative training academy.

The idea was born after my experience designing NAPA’s first-ever Master Class in 2022. I developed my own curriculum from over a decade of academic discourse. That course generated revenue and respect for the institution, but more importantly, it showed me the demand for new kinds of creative education. Our very first academic activity was an eight-hour masterclass with filmmaker Jami. Not a single person left the room. That’s the kind of immersive and transformative experience we want to create.

Q: Do you think enough platforms exist for young talent in Pakistan? What more can be done?

Platforms, as people imagine them, don’t really exist here. Young artists now have phones and can make two-minute films — that’s something. But the myth that someone will just ‘discover’ you and

put your face on a billboard is dangerous. Real platforms come from consistent, quality work. Right now, much of our theatre is in degeneration. There’s no strong lifeboat for young talent.

Q: What does “meaningful entertainment” mean to you in today’s digital age of viral trends and content overload?

For me, meaningful entertainment has to carry a message. We live in an age of endless, mindless scrolling. But once in a while, you stop. Why? Because something had depth, something touched you. That’s meaningful. And I’ll go further: it’s not just ‘meaningful,’ it has to be original. The moment you tell your own story, it becomes meaningful automatically. That’s what we lack today—originality.

Q: What advice would you like to give aspiring artists who want to enter this field?

Don’t chase advice. If you truly believe you belong in this field, just do it. But yes, listen to everyone. Sometimes the most unexpected feedback from a friend, a stranger and even domestic help can shift your perspective and improve your craft.

Theatre

Return Of Siachen on Stage

Anwar Maqsood’s Siachen presented in 2015, has made its way back to the stage, and with this revival comes a reminder of why the play first struck a chord with audiences. For years, critics of Maqsood’s theatrical ventures have questioned whether his work fits into the framework of “serious theatre,” often pointing to earlier productions like Ponay 14 August and Dharna as lacking the dramatic conflict essential to stagecraft. Yet, the return of Siachen, staged under the direction of Dawar Mehmood at the Arts Council, offers a counter-argument—one that combines satire with depth, humour and a humane aspect.

At its heart, the play pays homage to the Pakistani soldiers stationed on the Siachen Glacier, one of the most unforgiving battlefronts in the Karakoram where Pakistan and India have maintained a military presence since the 1980s. While Maqsood’s hallmark wit runs through the script—quick repartee, satirical digs, and clever wordplay—the core of the drama lies in exploring the psychological toll of separation from home and the relentless physical demands of surviving in such hostile terrain.

The narrative begins in darkness, with spotlights illuminating soldiers and their families grappling with the reality of duty before the scene shifts to the icy peaks of Siachen. A painted mountain backdrop and a lone tent create the setting for soldiers whose camaraderie and spirited exchanges drive much of the early humour. Their verbal sparring with unseen Indian troops delivers some of the liveliest moments, including the infamous “zaheen Sardar” quip, while Maqsood does not spare his own society from mockery—a soldier mistaking a white board for a peace sign only to discover it’s a Bahria Town advertisement earns loud laughter. The comic rhythm continues when an Indian soldier accidentally crosses over, triggering a series of sharp, playful interactions.

Gradually, however, the mood shifts. The battle scene, though intense, makes this argument forcefully, confronting the audience with the cost of violence. From a production standpoint, Siachen displays greater theatrical craft than Maqsood’s previous collaborations, with strong use of lighting, sound, and smooth transitions between scenes. If the set design had been broader to reflect the magnitude of its subject, it might have elevated the staging further, but the effort remains commendable.

With its return to the stage, Siachen demonstrates why it continues to resonate—it is at once funny and poignant, entertaining and thought-provoking. The production reaffirms Anwar Maqsood’s unique ability to merge satire with substance in the realm of Pakistani theater.

Theatre

A Satire That Hit the Heart

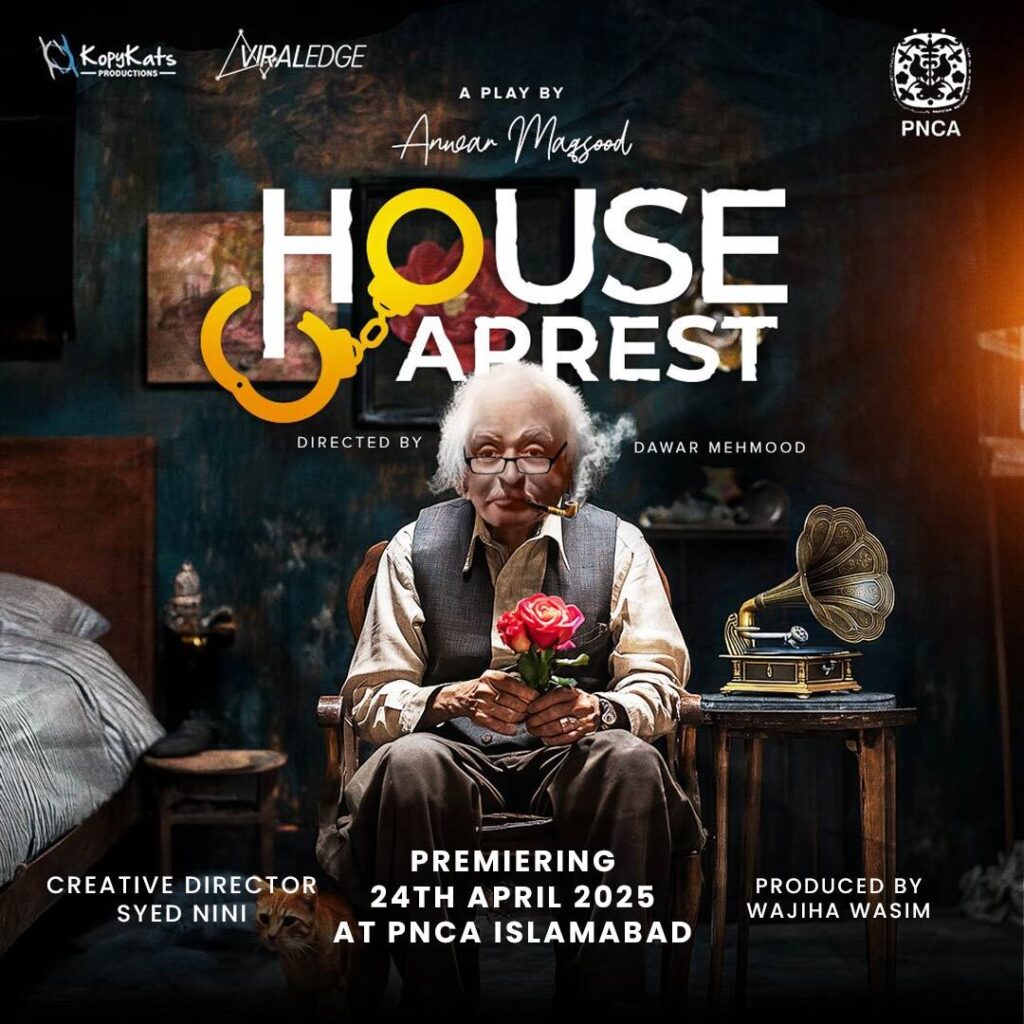

In a time where entertainment is often reduced to screens and scrolling, House Arrest by Anwar Maqsood breathes life back into the stage. Performed at the IBA City Campus Karachi, this political satire drew in crowds not just for its name, but for the promise of something meaningful beneath the laughter.

The play confined to one room, presents two elderly women seemingly forgotten by time and family. Their world is at a standstill, and memories are the only sustenance in the confines of the four walls that haven’t seen visitors for a long time. The title, House Arrest, couldn’t be more appropriate to their situation.

On the surface, it appears to be a domestic drama, an ongoing conflict between the old women and their materialistic son and daughter-in-law. But beneath that lies a scathing, satirical reflection of a broader reality. The obsession with ownership, the desperation for control and the pettiness of egos. In their arguments over a name on a gate, we see our own societal hierarchies, our personal wars for validation, and the illusion that money and power equals peace.

The brilliance of Anwar Maqsood lies in his layers. As the women remain ‘arrested’ in their own home, the audience is introduced to a parade of visitors: a robber, a retired judge, a former police officer and a disillusioned hockey player. Each is symbolic. Each a thread in the unraveling fabric of the society portrayed in the play. Together, they paint a bleak but bitingly humorous portrait of a nation where the powerful exploit, where the system has failed, and the common citizen is left caught in the crossfire.

The house isn’t just their prison. It’s a metaphor for the country. Its locked doors echo with stories of betrayal, of promises broken in the name of reform. And as the characters weave in and out, bringing their chaos and confessions, we’re left with an uncomfortable truth: perhaps we are all, in some way, under house arrest.

Yet, despite the weight of its message, House Arrest never feels preachy. Anwar Maqsood’s wit is razor-sharp, his humour disarming. He allows us to laugh before we realize what we’re laughing at.

One of the play’s most powerful moments comes in the form of a domestic brawl a comedic yet deeply moving scuffle between the women and their daughter-in-law. The movements bordering on gymnastics are brilliantly performed by the cousin and daughter-in-law. It’s chaotic, yes. But also cathartic. Because in that moment, the tension breaks. The truths spill out. And we are reminded why theatre remains such a vital art: it makes us feel and think.

The play had it’s humorous moments with laughter resonating in the hall unabashedly. The acting of the characters was superb, specially the main characters Shameen Tariq who played the role of Bee Amma and Raisa Raisani who played the role of Nasreen. But one felt the lack of cohesion in the presentation here and there. Was it due to the meddling of strong outside factors and censorship perhaps? Overall the play was a much needed injection for the Karachi crowd bring to mind the adage laughter is the best medicine.

Theatre

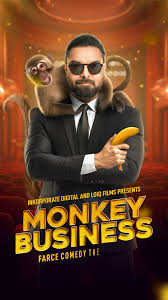

Monkey Business Swings

By Ayman Munaf

If you were wandering around the Karachi Arts Council recently, chances are you heard loud laughter echoing through the auditorium. It was the opening night of Monkey Business, the latest theatrical venture by Yasir Hussain — who wears multiple hats here as the writer, director, and lead actor. The play was a clever mix of farce, satire, and classic Karachi-style comedy that had the audience in stitches from start to finish.

At the centre of the chaos is Wasim (played by Yasir Hussain himself), a struggling actor whose glory days are behind him. He’s married to Sana (Yusra Irfan), a fiery, no-nonsense painter whose temper can be as bold as her brushstrokes. Adding to the mix is their tenant, Sherry (Umer Alam), an aspiring thespian with big dreams and a flair for drama.

Things start to spiral when Wasim receives a call from a stern-sounding representative (Bilal Yousufzai) from the Arts Council, investigating the disability funds Wasim’s been receiving. In a panic, Wasim stages an elaborate ruse, pretending to suffer from a physical ailment — complete with crutches and a limp. Meanwhile, news of a recent escape from a local asylum adds an unexpected layer of confusion to an already tangled web of lies and misunderstandings.

What follows is classic farce: mistaken identities, disguises, and even some impromptu dance numbers. Wasim and Sherry end up donning women’s clothes and shaking a leg to popular desi tunes in an attempt to keep their ruse alive.

Yasir Hussain’s performance as Wasim is a masterclass in comic timing. He’s at ease on stage, shifting effortlessly between the grounded and the ridiculous. Yusra Irfan holds her own as the fierce and feisty Sana, while Umer Alam’s Sherry brings an endearing goofiness that balances out the trio. Bilal Yousufzai, though in a supporting role, adds the perfect tension needed to push the story forward.

Visually and tonally, the play pays tribute to Karachi’s vibrant theatre scene from the 1980s and ’90s — a time when dance numbers, double entendres, and larger-than-life characters were all part of the fun. And while Monkey Business may feel nostalgic, it never feels dated. It uses the old tricks with a new flair.

There’s something refreshing about a play that doesn’t take itself too seriously, yet knows exactly what it wants to say. Monkey Business is that kind of experience. It was not here to preach or provoke deep reflection but to make you laugh until your sides hurt. But in doing so, it also gently nudge you to think about the trials of creative professionals, the absurdities of bureaucracy, and the fine line between reality and performance. In a world often too grim for its own good, Yasir Hussain delivers a much-needed dose of joy — chaotic, clever, and wonderfully theatrical.

-

Entertainment2 months ago

Entertainment2 months agoHundan: Touching the Core of Humanity

-

Business3 months ago

Business3 months agoZafar Masud: A Journey of Survival, Leadership and Purpose in Life

-

Cover story3 months ago

Cover story3 months agoKinza Hashmi: Tapping Emotional Depth

-

Bright Side3 months ago

The Bright Side

-

Business3 months ago

Business3 months agoA Roadmap to Pakistan’s Economic Revival

-

Travel3 months ago

Travel3 months agoRevisiting Karachi’s Interesting Places

-

Ramp Act3 months ago

Ramp Act

-

In Tune2 months ago

Faakhir Mehmood – Music Embedded in the Soul