Uncategorized

The Man Behind Pakistan’s Photography Evolution

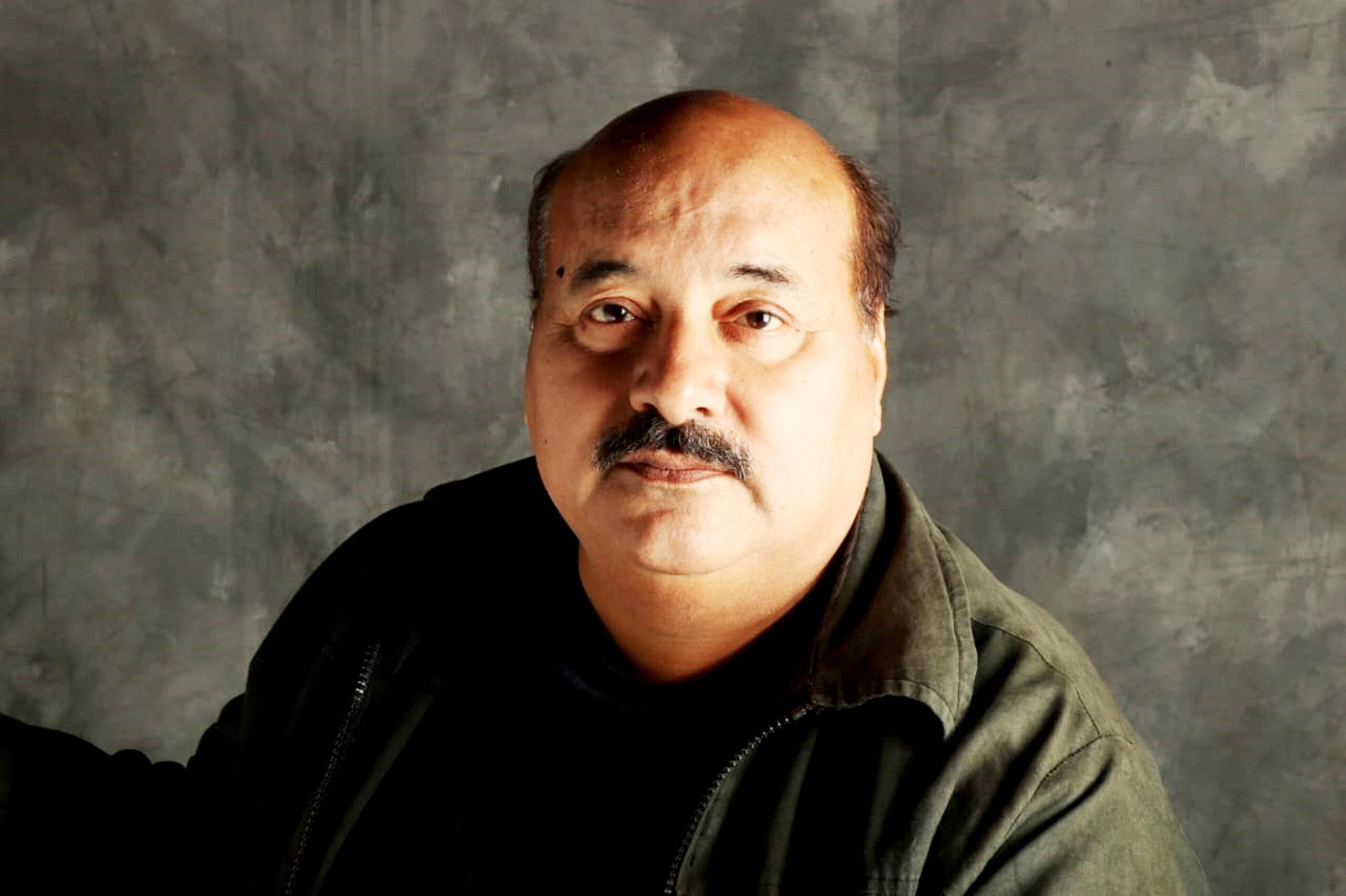

Recipient of the Tamgha-e-Imtiaz, Prof. Rahmatullah Khan has been a trailblazer in photography education in Pakistan. As the architect of the country’s first photography diploma, his contributions span across photojournalism, media arts, TV production, archaeology, cultural heritage. Teaching students the nuances of the evolving world of photography and his advice for aspiring photographers.

Can you share your journey into photography? What inspired you to pursue the field of photography?

R.K: My journey with photography started at the age of six when my elder brother gifted me a camera worth 110 rupees. That little piece of equipment sparked a lifelong passion. I always say, “Photography is my religion.” But passion alone wasn’t enough. Coming from a nawab family, my mother strongly opposed my career choice. She believed photography wasn’t a suitable path for someone from our background. I was determined, though, and refused to let societal expectations dictate my future.

An MBA in Marketing and I worked in computer marketing for ten years. However, something was always missing. One day, I made a bold decision—I left my corporate job and dedicated myself entirely to photography. I started teaching at the Pakistan American Cultural Center (PACC), and from that moment, there was no looking back. It’s been 36 years since I began teaching photography, and I still love every moment of it.

How did you become associated with Alliance Française de Karachi?

R.K: As my teaching career expanded, I started working at multiple institutions, including PACC. When I approached Alliance Française, they welcomed me aboard, and I eventually established my own art gallery here. At one point, I was teaching in six to seven universities simultaneously! Currently, I am pursuing a Ph.D. in Visual Anthropology of the Indus Civilization, a photography-based research project that—if completed—will be the only one of its kind in the world. It’s a thrilling challenge!

What were some challenges you faced as a photographer in Pakistan?

R.K: Every day is a challenge—not just for photographers, but for media professionals in general. I have taught TV production, film production, and video production at universities, and one of my biggest concerns is the lack of dedication among the younger generation. They get excited about the field but lose interest in just a few days. There’s a serious gap in career counseling—something that was once addressed at PACC by Dr. Falak Thawar. She had a Ph.D. in student career counseling, but after her passing away, the entire department shut down.

What are the key elements that make a compelling photograph?

R.K: It varies from photographer to photographer, but a great photograph should showcase both artistic vision and technical skill. Ansel Adams once said, “We don’t take photographs; we make photographs.” That’s an essential mindset. A photographer must compose the image with intention, paying close attention to lighting, angles and emotion.

With digital photography and AI on the rise, how do you think photography as an art form is evolving?

R.K: Technology will keep evolving, but photography will always remain photography. Cameras may become more advanced integrating AI features, but at the end of the day, the art lies in the hands of the photographer. I still develop my photographs in a darkroom, using traditional black-and-white techniques. I even import film and chemicals from Dubai because I believe there’s something special about analog photography that digital can’t replicate. I’ve also introduced a darkroom photography course to keep this tradition alive.

You have been recognized as an archaeology and heritage photographer. What draws you to these subjects?

R.K: I began my career with wildlife photography—long before it gained recognition. But wildlife photography requires an immense amount of time, so I transitioned into fashion photography. Eventually, I received an assignment to shoot heritage sites, and I never looked back.

I have traveled to China four times by road, cycling across entire provinces to document heritage sites. Unfortunately, in Pakistan, archaeology and heritage photography are underappreciated. Exhibitions happen here, but the real demand comes from international audiences.

What role does photography play in preserving Pakistan’s cultural heritage?

R.K: Photography is a powerful tool for preservation, but it requires people who truly care. Thirty years ago, I took my students to Makli Graveyard—a place rich in history. People mocked me, questioning why I was interested in photographing old tombs. But I saw it as an opportunity to document our heritage. Today, many realize the significance of such places, but back then, very few paid attention. The journey of photography education in Karachi has been remarkable. When I started teaching in 1988 at PACC, the field was still in its infancy. Over the years, I’ve played a key role in shaping photography education, especially in Karachi. Today, we offer internationally recognized diplomas at Alliance Française, providing students with a globally competitive edge.

What advice do you have for young photographers who want to turn their passion into a profession?

R.K: Practice, practice, practice! Photography is not just about technical skill—it’s about dedication. You must shoot every day, every week, and every month to refine your craft. Master the fundamentals—lighting, composition, and exposure. Your camera is just a tool; it’s your vision that makes the photograph. Creativity and technical expertise must go hand in hand.

For upcoming photographers, my advice is simple: stay consistent, stay curious, and never stop exploring.